Anatomy is a branch of biology that looks at how the body is put together. Anatomical science looks at the body as a collection of many different parts and tries to find out more about each one. This may not be a holistic way to look at the body, but the information can be very helpful when used in a more holistic way. Yoga anatomy is the science of anatomy as it applies to the practise of yoga, especially the practise of yoga asana.

Body parts or body functions?

Anatomy is the study of how the body is put together and how its parts fit together physically. Physiology is the study of how parts of the body work and how they work together. Consider the nervous system. Physiology is the study of how and why the nervous system sends messages. Anatomy is the study of where nerves are in their paths around joints or through bones.

In real life, anatomy is usually about bones and muscles, while physiology is usually about organs.

What do yoga teachers need to know about the body?

It takes time to learn about anatomy. If you try to take in too much information at once, it will seem ridiculously hard and frustrating. The best thing to do is read and learn what makes sense to you… and then come back later to read it again. Your understanding will get better as time goes on.

Anatomy is a very big area of science. You could spend years studying it, get a master’s degree, and win a few scientific awards, and you’d still be pretty sure there’s more to learn about how the body works.

You don’t have to be an expert or a scientist to understand anatomy well enough to use it in yoga. You just need to be interested, willing to learn, and interested.

Teaching Yoga Anatomy

The words used in anatomy

Sanskrit is the language most often used in yoga. Some people learn the Sanskrit names for yoga poses and other parts of the practise, while others learn words and names for the same things in their own language. The same thing is true about anatomy.

Latin is the main language of science, with some ancient Greek thrown in. Scientists from different countries were able to talk to each other and share their knowledge because they all spoke the same language.

You can learn a lot about anatomy for yoga without learning all the formal terms, just like you can do a Seated Forward Bend without remembering that it’s also called Paschimottanasana.

The most important rule of yoga anatomy is that everyone’s body is different.

This is an important part of anatomy that people often forget about. It’s very important information for people who do yoga and for people who teach yoga.

We all know that some people are taller or shorter than others, and that some have obvious differences like wider shoulders or bigger feet. But normal differences in the way the body is built can also change the proportions of the body, which has a direct effect on doing yoga asana.

Even if two people are the same height, one might have a shorter torso and longer legs than the other. The other could have a longer torso and shorter legs. When a person does Child’s Pose for the first time, their knees will be close to their shoulders. Their chin moves up towards their neck, and their forehead rests on the floor. The second person’s knees will be close to their lower ribs when they do Child’s Pose. They have their shoulders closer to the ground. This makes their face lie flatter to the floor, stops their chin from tucking in, and puts their nose first into the floor instead of letting their head rest on their forehead, which is more comfortable.

One way to show Child’s Pose

There are many poses that are different in this way. Anatomical differences include things like the length of a person’s legs or arms, the length of their torso, and the size of their muscles, all of which can change how they move. If a person is short and has big thighs, it will be even harder for them to do Eagle Pose (Garudasana) or Shoelace Pose (Gomukhasana). Even if their joints aren’t more flexible than the muscular person’s, those poses will be easier for someone with longer, thinner legs.

A joint’s range of motion can also be affected by another very common difference in the body. The hip joint, which connects the thigh to the pelvis and looks like a ball and socket, is the one that changes the most. The bone shape of the hip socket in the pelvis and the shape and orientation of the “ball” at the top of the leg can vary a lot and still be normal and healthy. This means that some people will be able to move their hips more or less in one or more directions. Practice and stretching can make it easier for muscles and ligaments to move, but they can’t change the bones in a joint. If you try to move a joint that is limited by bone, you could hurt yourself or even break it.

Anatomy of Yoga: Everything You Need to Know The bones.

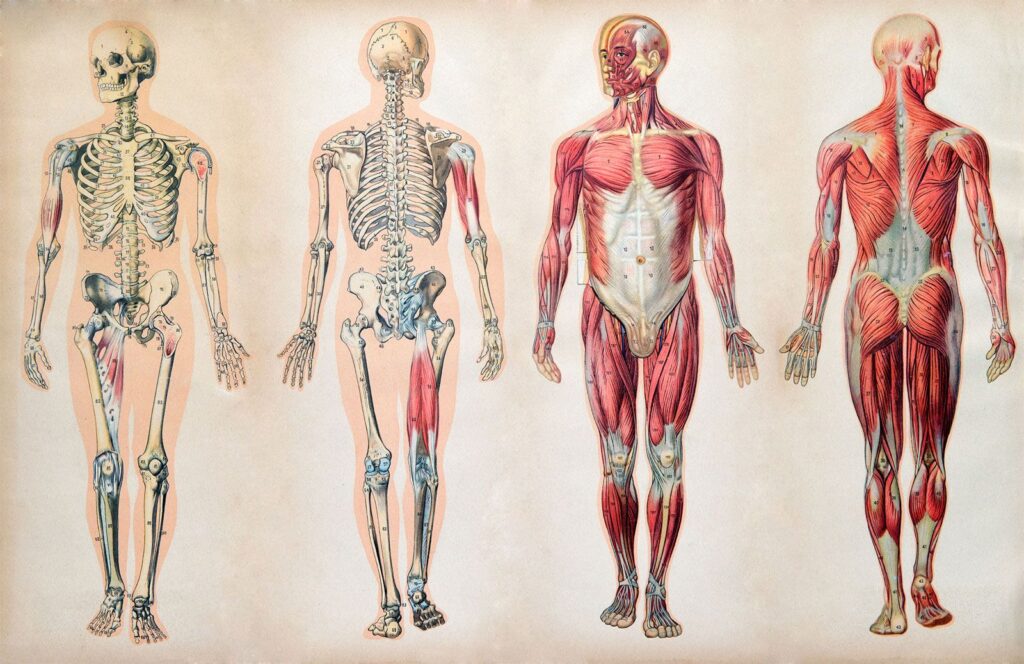

The skeleton of a person

There are about 206 bones in a person’s body (approximate because that too can vary between people). About a quarter of these bones are in the hands and feet, which each have an average of 53 bones.

One of the most important reasons to learn about our bones is that they support our muscles and help us move. Knowing the names of the major bones makes it much easier to talk about or study movements.

Joints are where two bones meet, and they are even more important to learn about when learning how to move. Each unique human has around 300 joints.

The axial skeleton is made up of the skull, spine, and ribcage. Our limbs move around on top of them. The pelvis, shoulder girdle, and limbs all connect to this base. Together, these parts are called the appendicular skeleton.

In yoga, the spine and ribcage move, which is part of the axial skeleton. There are three different parts to the spine, each with its own shape and way of moving. The neck, the upper back, and the lower back are all parts of the spine (lower back). During yoga asana, the three parts of the spine work together to make the required range of motion.

How the spine is made

There are seven bones in the neck, which is also called the cervical spine. Most of the bending forward and backward (flexion and extension) in the cervical spine comes from the joint where the top of the head meets the first vertebra. The joint between the first and second vertebrae is responsible for most of the neck’s ability to turn. The remaining joints in the cervical spine can move in more ways than any other part of the spine. This means that the cervical spine can bend more forward, backward, and to the side than any other part of the spine.

When it comes to joints, more flexibility means more risk. No matter what, you should never force your neck to move.

Between each vertebra is a shock-absorbing pad called an intervertebral disc. The discs in the cervical spine are the thinnest and smallest. Between the skull, the first vertebra, and the second vertebra, there are no discs.

Headstands, shoulderstands, and other poses that put weight on the neck should be done carefully, with close attention to how the body feels and a gradual buildup of the poses. The spine is made to support the body’s weight through the large, strong vertebrae and thick, resilient discs of the lower back. However, with care and common sense, it is possible to safely practise inversions that put the body’s weight through the small vertebra of the neck.

The thoracic spine and ribcage (upper back)

The ribcage is made up of 12 (or sometimes 13) pairs of ribs that connect to the spine at the back. At the front of the ribcage, the upper ribs connect to each other and to the breastbone, also called the sternum. The two ribs at the bottom are much shorter and don’t connect in front. The main jobs of the ribcage are:

protecting the organs in the chest

Helping you breathe. Your lungs don’t move on their own. Our muscles move our ribs and diaphragm, which causes your lungs to expand and contract.

The vertebrae in your upper back are called thoracic. There are twelve of them, and each one has a bony bump on each side where the ribs can connect. The joints between the vertebrae and the shape of the bones where the ribs connect limit how much the thoracic spine can move. The thoracic spine can’t bend as far forward or backward as the neck or lower back can. On the other hand, it twists more than any other part of the spine.

Asanas that make the thoracic spine and ribcage more flexible can help you breathe better and lessen back pain, arm and shoulder pain, and headaches.

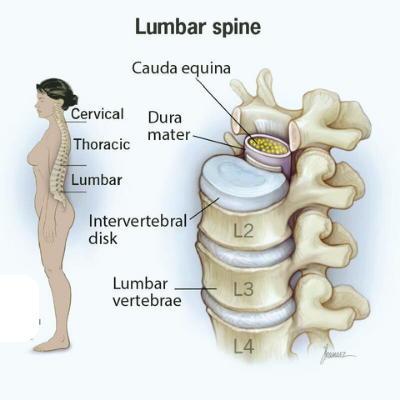

Lower back, also called lumbar spine

The bottom part of the spine is made up of five vertebrae. They are the largest vertebrae and are separated by thick intervertebral discs, which support the weight of the upper back and upper body.

The lumbar spine can bend backwards (called “extension”) the most, but it can also bend forwards, to the side, and even rotate a little bit.

Even though the lumbar spine is strong and flexible, it shouldn’t be pushed past its natural limits. Forward bends are common and useful yoga poses, so both students and teachers should know how to do them safely.

Spine and pelvis

Yoga safety tips for the spine

Spinal cord: The spine makes a bone tunnel around the spinal cord to protect it. At each joint between vertebrae, there is a space for a bundle of nerves to connect the spinal cord to the rest of the body. When the bones or joints of the spine are hurt, they can hurt these nerves directly or cause swelling, which puts pressure on the nerves.

Because the spine is so close to the nerves, it is important to treat it with care and pay attention to what the body tells you. Too much movement through the spinal joints can cause pain, tingling, or numbness in the areas where the nerves go. Pressure in the upper back could cause a feeling in the hand, and pressure in the lower back could cause a feeling in the leg or foot. Bringing on these symptoms is bad for the nerve and not a good way to practise yoga. It’s important to give each person time to become more flexible and to respect their physical limits.

Curves in the spine: Each part of the spine is naturally bent. The neck curve is in, the upper back curve is out, and the lower back curve is in. Even the pelvis, which has another outward curve below the lower spine, follows this pattern. These curves help you stay balanced, spread your weight evenly, and stand up straight. They are normal and natural, and people have different levels of them, so there is no need to try to “fix” them. There are many reasons why your spine or the spine of one of your students might be curved in an odd way. A doctor should be asked for advice and to make sure everything is safe.

Spinal mobility: Remember that the upper back should do most of the turning. The neck can move a lot, but it shouldn’t be forced into dangerously wide ranges of motion. If it’s hard to get into an asana, pay attention to where movement seems to be blocked. It is better to work on increasing range of motion in the area that is limited than to let other parts of the spine make up for one area that is not flexible (taking into account any injuries or conditions).

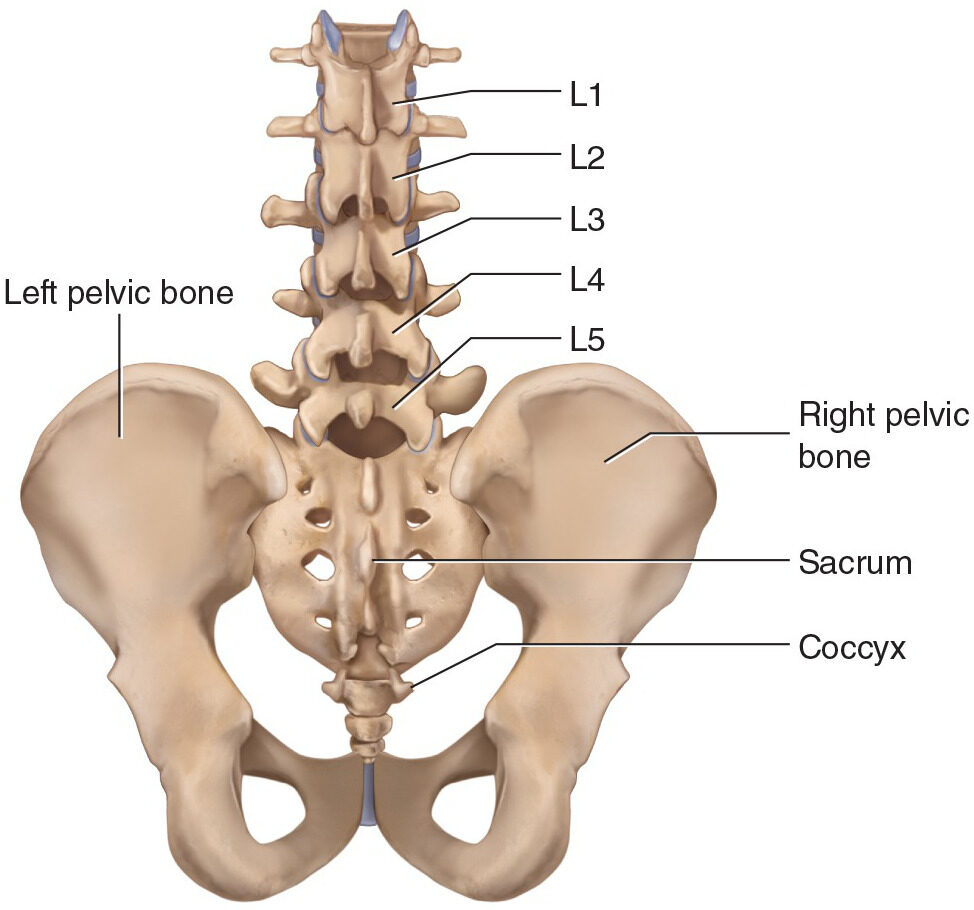

The hips

The pelvis is a circle of bones that holds up the spine and the rest of the body. The sacrum is the big triangular bone under the lumbar spine. Below it is the small coccyx, also called the tailbone. The pelvic bones on each side of the sacrum circle around and meet in the middle of the front. The joint in the middle of the front of the pelvis helps keep it stable and shouldn’t move much. The sacro-iliac joints, which are where the pelvis and sacrum meet in the back, don’t move much. It can be helpful to move these joints slowly and gently. The purpose of Supta Virasana, or “Reclining Hero Pose,” is to move the sacro-iliac joint.

Yoga safety tip: keep your pelvic area stable

Care should be taken with pelvic joint mobility because encouraging mobility can easily lead to instability, which can cause a lot of pain during practise or in everyday life. People who are hypermobile and women who are pregnant or just had a baby are more likely to have problems with pelvic instability.

Some poses can also put uneven pressure on the sacro-iliac joints, which can be dangerous or painful for people with less stability. Weight-bearing poses with uneven leg positions put uneven pressure on the pelvic joints. This is especially true if the legs are spread far apart.

Joints in the bones

Joints can move in many different ways because they come in different shapes. Synovial joints are the places where the body moves the most. There is a lubricating fluid called synovial fluid in these joints that coats the cartilage at the end of each bone and helps the bones move smoothly against each other. A capsule of connective tissue and a number of ligaments hold the joints together.

These joints are divided into different types based on their shape, which determines how they can move:

Only one way can be bent at a hinge joint (eg. elbow)

Pivot joints only let things turn (eg. joint between top two vertebra of the neck)

Saddle joints let things bend forward, backward, and to the side (eg. base of thumb)

Condyloid joints bend the same way saddle joints do, but they have less range of motion (eg. between radius and the carpal bones)

Plane joints can slide or move back and forth (eg. the sacroiliac joint – back of pelvis)

Joints with ball and socket can move in all directions (eg. shoulder and hip)

Knee joint

There are two other kinds of joints that yoga practitioners might want to know about.

Fibrous joints aren’t what most people think of when they think of a joint, and they include the suture lines of the skull. There are two more important fibrous joints for you. Strong connective tissues and fascia hold the bone pairs together in the forearm and lower leg, but they still allow some movement when the wrist and ankle move. If a person is forced to move their wrists or ankles beyond what is safe, they could hurt these tissues.

Cartilaginous joints have joint cartilage but no synovial fluid. Some of them, like the intervertebral joints of the spine, may also have a fibrous disc that acts as a shock absorber and makes room for movement.

The yoga joints

Joints should only move in the directions for which they were made. If you try to force other movements, you could hurt yourself. Asana progressions that put pressure on joints in more than one direction should be done with care. Some versions of Pidgeon Pose, for example, require knee rotation, which is a very limited movement.

People with the same joints have a little bit different shapes. This means that the shape of a person’s bones at birth can make them more flexible than someone else.

When you stretch a joint beyond its normal limits, the ligaments and connective tissue that are supposed to support and protect the joint can become stretched and weak.

Popping and clicking sounds during normal movement don’t always mean that someone is hurt. It usually means that the joint is a little bit unstable and that the muscles around the joint could use some work.

It’s not a good idea to “crack” joints on purpose often, because it can wear down

the joint surfaces and weaken the tissues that support the joint.

Strong muscles that work well together protect our joints. To keep a joint safe, increasing its range of motion should always go hand in hand with building muscle strength and getting a handle on the new range of motion.

Hyperflexion and hyperextension are movements that go past what a joint can normally do. This can cause tears, damage, or dislocations in the ligaments.

Some people are more flexible than others by nature, but that doesn’t mean their joints are safe when they are too bent or too straight. They are more likely to get hurt because their joints aren’t protected by connective tissue that stops them from moving more than normal.

Yoga anatomy – muscles

The body has more than 600 different muscles. We don’t have to know all of them in order to do yoga or teach it.

Some muscles, like the heart and the muscles that move food through the digestive tract, are not under our conscious control. These muscles are called involuntary muscles. Voluntary muscles are the ones we use to move around on purpose. Some, like the muscles that help you breathe, can be controlled both by you and by your body.

Each muscle that moves our bones has a place where it starts and a place where it ends. These are called the origin and insertion. When a muscle contracts, it moves the body in a certain way. This is called the muscle’s action. If a muscle crosses a joint, it will move that joint. Several things make this simple idea hard to understand:

Some muscles go through more than one joint.

Some muscles can move a joint in more than one way, such as by bending it and turning it.

Several muscles can work together to make a certain movement.

Muscles shorten (contract) to move, but they can also work while lengthening to control where the movement goes when it goes back.

In a yoga pose, the same joint often moves in more than one way at the same time.

Yoga anatomy – fascia

Fascia is a very important part of both the human body and yoga anatomy. It is made up of connective tissues that work together to form a web that supports and links everything in our bodies. There is fascia under our skin, fascia around our organs and muscles, and a thin web of fascia around the bundles of fibres inside each muscle. Fascial tissue can be thick and strong, or it can be very thin.

When the body moves, so does the fascia. If fascia isn’t moved often, it starts to stick together, which makes the body stiff. Since fascia doesn’t have a blood supply, it also needs movement to get water. Dehydrated fascia also makes you less flexible and is thought to be the cause of many of the signs that people think come with getting older and making it hard to move around.

The best way to keep fascia healthy is to move and stand in many different ways on a regular basis. This is a perfect description of yoga practise. Just like a car seatbelt, fascia will stretch when you move slowly, but it will stop when you move quickly. Because of this, slow-flowing poses and poses that are held for a long time are good ways to improve flexibility through the fascia.

How to Avoid Getting Hurt in Yoga

Take note of the tips above about how to protect your back and pelvis.

Always start a physical yoga practise by warming up. Warming up makes your muscles more coordinated and quick, which makes them much better at protecting themselves and your joints. It also gets more blood flowing and gets muscles ready for more activity and movement in a safe and effective way. Gentle Sun Salutations are a great way to warm up before doing yoga.

Remember that each person’s natural alignment in an asana is likely to be different because of differences in bones, joints, strength, fitness, flexibility, and other things. Each person should practise in a way that helps them improve, not to reach a made-up ideal of a pose. This is also true for how long a pose is held.

Progress is unique to individuals. With practise, a person can get better at many things, such as flexibility, cardiovascular fitness, and muscle and bone strength. To avoid injury, you should make changes slowly and carefully. Most overuse injuries happen after weeks of doing too much, not during the first time you do too much. The length of time a pose is held, the range of motion used in a pose, or the practise of more complex poses are all ways in which a pose can progress.

If someone hasn’t worked out in a while, they will need to start slowly and work their way back up to where they were. If you don’t use your strength, endurance, or other skills often, your body will lose them.

Rest is important for both avoiding injuries and getting stronger. When you practise, you push your body’s tissues, but when you rest, they build up and fix themselves to make them stronger. Challenge and rest are both important for making progress. People have different needs for challenge and for how much they can do. The length of a practise, the time between practises, and the number of rest days built into a week’s schedule all show how much rest a person needs. Also, it’s important to get enough rest.

The study of anatomy helps us understand how each yoga pose affects the body. Based on how bones, joints, muscles, and fascia are put together, we can see that every human body has these things in common, but each body is also different. For each person’s body to be challenged, strengthened, and cared for, their practise will look different.

Yoga, which aims for unity, requires us to be aware of these differences. Everyone can practise yoga together, and each asana can be done in its own unique way.

The best books on yoga anatomy

Functional Anatomy of Yoga by David Keil

In the beginning, Keil says, “If you have done asana every day for at least an hour for 10 years or more, you definitely know how your body works pretty well. Even if you don’t know the technical names or details of the body’s parts, your kinesthetic knowledge is a very real and powerful way to understand the body.

So, his book is a companion to the knowledge we gain from asana practise, and it may help us understand some of the strange things we feel (or see others experiencing).

This book is one of the more recent, well-known anatomy books. It came out in 2014. In it, Keil breaks down the anatomy of each joint in the body. He talks about each joint’s range of motion, the way its connective tissues are set up, possible injuries, and how different people’s skeletons are made.

The second part of the book is about understanding how the body works in different types of asanas, such as forward bends, external hip rotation (think warrior 2), twists, arm balances, and backbends. In these parts, he gives examples of a few different poses, but he doesn’t spend a lot of time going into detail about the anatomy of each traditional yoga pose.

In a Nutshell: Learn about all of the joints and body parts in different yoga poses.

Yoga Anatomy by Leslie Kaminoff

Kaminoff starts the book by saying, “Yoga practise puts a lot of emphasis on the connection between the breath and the spine, so I will pay special attention to those systems.”

Kaminoff is a world-famous expert on yoga anatomy and breathing, following in the footsteps of T.K.V. Desikachar. His book Yoga Anatomy, which came out in 2007 and has since been updated with a second edition, breaks down the anatomy of many of the most common yoga poses, or asanas. It also has chapters at the beginning about how breathing works and how the spine works.

With the help of detailed drawings of each pose, readers can see which muscles are being used and stretched in each pose. There are also obstacles, breathing techniques, and the Sanskrit name for each pose (if learning Sanskrit names for poses is something that floats your boat).

Learn which muscles are used in each pose and how to breathe most effectively during practise.

The Key Muscles of Yoga: Scientific Keys Volume 1 by Ray Long

Ray Long is a board-certified orthopaedic surgeon and the founder of Bandha yoga, which has its roots in the Iyengar tradition of yoga asana. Chris Macivor’s digital illustrations of the skeleton and connective tissues in his books (yes, there are a lot of them) are beautiful (muscles, tendons, ligaments, etc.).

The first part of the book is about the skeleton. We learn the names of the major bones in the body, how joints work, and what connective tissues help hold the skeleton in place and let it move.

This includes how muscles tighten and loosen. The meat of the book is broken up into chapters about different muscles, starting with the big ones in the hips, buttocks, and legs. Information about each muscle is given, such as where it starts and where it ends (its origin and insertion), what other muscles help it work, and what it can do.

Long also has helpful self-test sections in which he gives the reader diagrams to label.

In a Nutshell: Learn the names of the body’s major bones and muscles, as well as how each muscle works when the body moves in different ways.

The Key Poses of Yoga: Scientific Keys Volume 2 by Ray Long

The Key Poses of Yoga has digital illustrations by Chris Macivor, just like volume 1.

Starting with theory, Long gives detailed information on the biomechanics of stretching, such as what muscles are made of and how they work with the nervous system when they are asked to do work (i.e. strengthen or stretch).

The second, and more important, part of the book explains how each yoga pose strikes a balance between bringing muscles together and getting them to work. The red and blue colours in the pictures of the postures show which muscles are used and how they are used in each pose.

Long calls each muscle by name in this book, so it’s important to either know the names of the muscles already or have a guide that can help fill in the blanks (his first volume is a great option for this).

Learn about the biomechanics of stretching and how different yoga poses use different muscles.

Yoga of the Subtle Body by Tias Little

Little says in the book’s introduction, “There are a lot of books on yoga philosophy and a lot of books on anatomy, but there aren’t many that combine the two.” I’ve always been interested in how the glands, connective tissues, and organs of the body relate to the mystical anatomy that is talked about in many old yoga texts. My goal for this book is to help people understand how metaphysical ideas affect the body and to give them a sense of the subtle body through guided exercises, meditations, and reflections.

Little’s approach to anatomy is a holistic one that takes into account the organs, glands, and even the mind. This helps us understand how and why we do yoga.

He splits his book into seven parts that correspond to the seven chakras, which are different nerve centres along the spine called “spinning wheels.” Little looks at the best anatomy and health of each of these parts, starting with the pelvis and moving up to the top of the head.

Because this book talks about parts of the body that we can’t see, it is not about learning how to hold each body part in a certain way. Instead, the idea is that if we really understand what this book is about, our practise and the way we use our bodies will naturally change to be more in line with optimal health.

In a Nutshell: Use the chakras to learn about how our organs, glands, and mind-stuff work best (thoughts, sensations, perceptions).

Yoga Sequencing: Designing Transformative Yoga Classes by Mark Stephens

Stephens says that doing yoga and teaching yoga are inextricably linked in the first sentence of the introduction. This shows that doing yoga and teaching yoga are not two different things or sets of knowledge. Instead, they are the same thing. So, any information marketed to yoga teachers is also useful and useful to anyone who practises yoga, even if they don’t want to teach.

In this book, Stephens breaks down the different types of poses in the asana practise to show us the best ways to move our bodies.

The first section, which is divided into five parts, is about the foundations and principles of movements, the arc structure of a yoga class, sequencing within and across asana families, and understanding verbal cues and instructions. In the second section, we look at how practises are made for beginning, intermediate, and advanced students. In the third part, we look at yoga for children, women with special needs, seniors, and other groups or situations. Part four talks about emotional and mental health, chakras, and ayurveda. Part five ties together what you’ve learned in the first four parts.

This book is especially helpful for people who want to learn how to do yoga on their own and how to position poses to get the most out of them.

Learn how to put poses in order within and between asana families (i.e. backbends, forward bends, twists, inversions, etc.)

Faq

1 Why is it important to learn about the body’s anatomy when doing yoga?

Learning about the body’s anatomy can help practitioners get their bodies in the right position, avoid getting hurt, and get stronger and more flexible overall. By understanding how the body moves and works mechanically, practitioners can make their work fit the needs and goals of each person. They can also learn more about their bodies and what they can and can’t do. This can help them work more mindfully and smartly in their practise.

2 How do different yoga positions affect different muscles, joints, and organs?

Different yoga poses have different effects on different muscles, joints, and organs in the body. For example, standing poses like Warrior II can strengthen the legs and hips, while backbends like Cobra can stretch and strengthen the spine. Forward folds can help lengthen the hamstrings and release tension in the back, while inversions like Headstand can improve circulation and reduce stress.

3 What are some common injuries that can happen when you do yoga, and how can knowing about the body help you avoid them?

Strains, sprains, and overuse injuries are common injuries that can happen when doing yoga. By knowing how the body works, practitioners can work safely and smartly within their own limits, which can help prevent these kinds of injuries. For instance, a yogi with tight hamstrings might need to change some poses to avoid strain, while a yogi with shoulder injuries might need to stay away from certain inversions.

4 What does the breath do in yoga, and what does it have to do with the body’s structure?

The breath is one of the most important parts of yoga. It helps you become more aware, focused, and relaxed. As the diaphragm, lungs, and respiratory muscles work together to support healthy breathing patterns, there is a close connection between the body’s structure and the way it breathes.

5 How does doing yoga affect the nervous system, and what does the nervous system have to do with anatomy?

Yoga can have a big effect on your nervous system by helping you relax and lowering your stress levels. The brain, spinal cord, and nerves are all complex parts of the body that work together to control how the body reacts to stress. This is how the nervous system is related to anatomy.

6 What are some specific alignment cues that a yoga teacher might use, and how do these cues relate to the body’s structure?

In a yoga class, teachers might tell students to engage their core, lengthen their spine, and rotate their shoulders outward. These cues have to do with the body’s structure because they help keep the body in the right position and prevent injury.

7 What are some of the most important muscles used in common yoga poses, and how do these muscles work together to keep the pose in place?

The quadriceps, hamstrings, glutes, and core muscles are some of the most important muscles used in common yoga poses. These muscles work together to keep the pose in place by making it stable, strong, and flexible.

8 What is the connection between the connective tissue, or fascia, in the body and yoga?

Fascia is a type of connective tissue that wraps around muscles, bones, and organs and helps keep them in place. In yoga, stretching and lengthening the fascia can help increase flexibility and mobility, reduce tension and stiffness, and promote healthy movement patterns.

9 What’s the difference between bending and stretching? How do these movements relate to the body’s anatomy in yoga?

In yoga practise, bending and stretching are two basic body movements that relate to the anatomy of the body. Flexion is when a joint bends, while extension is when a joint straightens. Figuring out how these things move

10 What are some ways that knowing more about anatomy can help a person get more out of their yoga practise?

One’s yoga practise can be improved in many ways by learning more about anatomy. First, it can help keep people from getting hurt by letting them align their bodies correctly in each pose and avoid putting too much pressure on certain muscles or joints. Second, it can help people become more aware of their bodies and how they move, which can lead to more mindful practises. Also, knowing how the body works can help you learn more about the energetic and subtle parts of yoga, such as the chakras and nadis.

11 What are some of the most common myths about the anatomy of yoga, and how can a better understanding of this subject help to dispel these myths?

People often think that flexibility is the most important thing for success in yoga, but that’s not true. In reality, strength, stability, and proper alignment are just as important for a safe and effective practise. Another myth is that yoga can heal any kind of physical problem. In reality, yoga is not a replacement for medical care. By giving yoga practitioners a more complete picture of how the practise works on the body, a better understanding of yoga anatomy can help dispel these myths.

12 How does yoga affect the cardiovascular system, and what does it have to do with anatomy?

Yoga can help the cardiovascular system in a number of ways, such as by lowering blood pressure, improving circulation, and lowering the risk of heart disease. The heart and blood vessels are important parts of the circulatory system, which is in charge of getting oxygen and nutrients to the body’s tissues. This is why cardiovascular health and anatomy are related. Yoga can strengthen the heart and blood vessels, which can improve the overall health of the heart and blood vessels. Also, a lot of yoga poses involve turning on the parasympathetic nervous system, which can help lower stress and lower the risk of heart problems caused by stress.